Implementing SOPs

What are SOPs?

Firstly what are SOPs? Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) are simply a specific way of getting things done and maintaining a steady consistent process, breaking down the most complex scenarios so even a novice can complete it. They are part of why, aviation is as safe as it is today.

In aviation, SOPs are required as part of strict procedures that are defined (usually by a flight operations department) covering every aspect of flight activity and encompassing normal, abnormal and emergency situations. This wide range of detailed procedures and checklists is essential because of the large number of situations which a pilot can face, especially in the IFR single pilot environment. Although these procedures are written down in checklists, aircraft flight manuals and quick reference handbooks, pilots must be able to perform certain vital actions from memory, referring to the written procedure later to confirm that the correct action has been taken.

It’s no surprise you’ll even find SOPs in most businesses and even your very own workplace may have SOPs, especially HR who will follow the process to the letter of the law. I even remember when I was studying at school during my flight simulator days on VATSIM, using aircraft from PMDG, and FS LABS you’d have manuals and plenty of information to assist in learning the ropes and following SOPs.

In a dual cockpit environment this is important with two pilots, both with different personalities and abilities, but both with the same ultimate aim, to fly safely, efficiently and responsibly. Standardising operating procedures is a proven safety tool for commercial operators. This is arguably the most significant difference between commercial operations and general aviation when it comes to training, testing, and cockpit cultures. Perhaps that’s a model for the rest of us to follow in General Aviation?

Why SOPs?

SOPs create consistency in how processes and tasks are performed, thus creating a safer environment, and reducing the odds of accidents. This is because tasks are well written through clear communication, and higher standards.

In aviation – adhering to standard operating procedures (SOPs) is a personal quality that can profoundly influence flight safety, and it starts from good pre-flight preparations. It’s important to understand that research has shown, that strict adherence to SOPs, including always effectively running normal checklists, is an effective method to enhance the safety of flight operations by preventing or mitigating pilot errors and by anticipating or managing operational threats.

Quite simply SOPs are a way of standardising the tasks and duties of pilots for each flight phase, including what to do and when to do it. In the commercial industry; establishing and following SOPs is an important part of the implementation of good crew resource management, colloquially known as CRM.

Are they relevant to SEP/SP IFR?

While piloting IFR is inheritably safer than vanilla PPL flying, through significant experience and training. Single pilot IFR or SP-IFR is one of the toughest, and busiest, tasks in all of piloting. You have to do everything that two pilots do in commercial airline operations, along with having to deal with the added distraction of passengers or equipment failures and severe weather hazardous to safe flight, i.e. unexpected Thunderstorms without the technology that an advanced aircraft incorporates, such as weather radar with wind shear prediction.

Whilst there’s significant importance regarding the pre-flight aspects of an IFR flight, there should be in-flight actions, such as recalculating fuel, checking weather routing ahead and preparing for those times when unexpected weather or malfunctions occur. SOPs would outline all of these details.

In the IFR environment, having sources of information and data to make it safer than it currently is – is an absolute no-brainer, and highly relevant – considering millions of miles in this format are conducted every day safely in the airline industry.

Preparation keeps problems from compounding when the unexpected happens, having a routine will help speed up the response and thus having a well-rehearsed routine and structure will aid in flight safety.

Why I’m developing them?

After gaining my Instrument Rating, COVID constricted my initial flights to the UK only and any international trip I did was pretty local and within 2-3 hours. Despite 35 hours of local training and the ATO part being rather intense with the weather, most flights post IR issues were benign.

I developed a checklist on a double-sided A4 and a short time later an A5 quick reference, laminated for my kneeboard to aid in in-flight planning and performance. This is all well and good, till having no means of a structure nor an organisation to use them. Additionally, I had since adapted my PLOG for the longer flights so I had a paper backup of the relevant flight plan info.

In June 2022, once worldwide COVID restrictions had firmly been lifted I flew with a fellow IFR pilot to the Czech Republic and returned via Germany. On the flight to Prague, we had 3 hours of avoiding Thunderstorms and convective build-ups in what was a relatively benign point-to-point flight. In the final hour of this sector, things became interesting, frontal IMC that we couldn’t outclimb and a fairly low icing level for Summer (10000ft) prevailed from the Czech FIR boundary till landing.

Because of a lack of SOPs, and a true understanding of a proper brief well before the approach – things quickly fell apart, although a safe outcome concluded, fellow PPL SEP IR veteran Stefan gave me some tips and insight that became a catalyst for me to re-develop my checklists and introduce some SOPs.

That saying practice makes perfect couldn’t speak louder than words. I was pretty organised, but things needed tweaking and I could still maintain a LPC (Less paper cockpit). Having a reference point through SOPs could enhance flight safety for me and others around me.

Reducing the risks

Since most general aviation IFR operations are flown with just one single pilot, decision-making and process are more likely to break down than those typically flown in dual pilot operations often flown in a different environment with turbine-powered aircraft and for the majority of the time on advanced autopilots.

To ensure peak performance, prior preparation is key to reducing the workload and preventing problems from compounding when unexpected scenarios happen. We saw this when arriving in Prague, if we had briefed the weather conditions better and had a plan – things might have been easier.

Having a better structure for flight briefings such as the approach brief would have meant a more relaxed arrival into Ruzyně, rather than the momentary overload that occurred with icing build-up in IMC, and build-ups throwing the aircraft about.

Having Stefan an experienced veteran PPL-IR onboard meant rewriting the rulebook for my future IFR flights, thus reducing the risks. As the journey continued I briefed better and we were ahead of the game, despite the convective summer providing additional challenges – thankfully it all worked out in the end.

I was now looking at developing SOPs, a new checklist format and reducing the risk of the wheels coming off.

NCO & AMC

As a non-commercial operator, you need to be familiar with the EASA Basic Regulation and the Air Operations Regulations, particularly Annex VII (Part-NCO).

Annex VII the draft Commission Regulation (europa.eu)

These are the rules and regulations you have to fly your aircraft in. It’s extremely complex and lengthy, not only that you have to fly the aircraft within the envelope of the AFM (Aircraft Flight Manual) – which coincidentally is approved by the same agency that builds the regulations.

When I looked at the two together, there’s flying the aircraft and then there’s flying to a set standard under the Instrument Rating which no amount of theory or study can prepare you for. However, when operating within the complexities of an IFR flight, having an understanding of all the regulations and what you can or can’t do is a challenge for the best of us. Thankfully there’s an unrivalled knowledge base online from two websites; called EuroGA and PPL IR that has a wealth of experienced members, some that are on both forums and have amassed hundreds of thousands of hours of experience in GA IFR in Europe providing the expertise to prosper as a pilot, outside the guided scope of an instructor or ATO.

None of us fly regularly enough to have the underpinning knowledge to navigate the turbulence that is expected of us as pilots, albeit even the commercial ops guys have iPads with a database of information to assist in operations, and that’s at the complexity of CAT ops with two, three or even four very experienced crew members with years of experience behind them.

Developing a framework

So after the big trip to Prague & Germany, I looked at developing a framework that I could potentially follow. It’s a huge amount of work to get it off the ground, but as of typing, I am roughly 50-55% of the way through developing all of the framework compromising of the AFM and NCO and any details of the UK AIP that can assist in the development of working towards a set standard.

Developing it in the form of a framework means that it’s simple, accurate, easy to use, comprehensible and effective, which is the whole point of implementing SOPs. Coincidentally this works for CAT-OPS where the “accident rate” is 1.21 for global air carriers (1 accident every 830,000 flights) which means creating SOPs is a no-brainer.

This is however, a huge undertaking, resulting in many hours of research and time spent creating the required documentation and sub-parts so that the wide range and source of information is easily accessible rather than being disseminated all over.

First things first was the update of the;

- Normal Ops Checklist

As aforementioned, I developed this as soon as I got my IR; you can read a little bit more about the inception of the checklist in one of my first-ever BLOGs.

This was followed by the first creation of;

- Abnormal OPS Checklists

- Emergency OPS Checklists

These had to be very specific to IFR operations and that environment. More on that in the next chapter.

For more details – Publications with titles containing checklists can be found on the UK CAA website.

Then work began on the IFR manual & and an updated version of the QRH that I created in the early stages of utilising my IR. The IFR manual will contain everything because that is the bible of all the information I am sourcing to create all aspects used in flight.

Creating the Documents

Aircraft go through a complicated process for certification to meet the airworthiness requirements and part of this process is the creation of manuals in the form of the AOM or FCOM. The Aircraft Operating Manuals and or Flight Crew Operating Manuals are the primary reference material for the operation of an aircraft under normal, abnormal, and emergency conditions.

Creating these documents does not change any procedure that is already set by the Aircraft Manufacture, it purely consolidates all the information from a wide range of sources and ensures that the aircraft is operated to the required standard for Instrument Flight – of which some are more stringent than that in VFR flight when the aircraft is operated IFR in the Airways system.

AMC1 to NCO.GEN.105(c) states “The pilot-in-command should use the latest checklists provided by the manufacturer.” but you may use your own under AltMoC; Alternate Means of Compliance without approval (NCO.GEN.101). The only requirement is that you should follow the operating procedures in the AFM (NCO.GEN.105(a)(3), referring to Basic Regulation, Annex IV, 1.b), but you can still do that using your own checklists that you have created.

Most if not all manufacturer checklists do not include IFR-related checks. Sources of information that I used to create the documentation were the NATS AIP, CAA SafetySense, Diamond Aircraft, EASA (specifically NCO), PPL IR and Eurocontrol.

Normal OPS Checklist

Checklists support pilot airmanship and memory and ensure that all required actions are performed without omission in an orderly fashion.

There are usually two types of checklists:

- Challenge & Response checklists

- Read and do lists

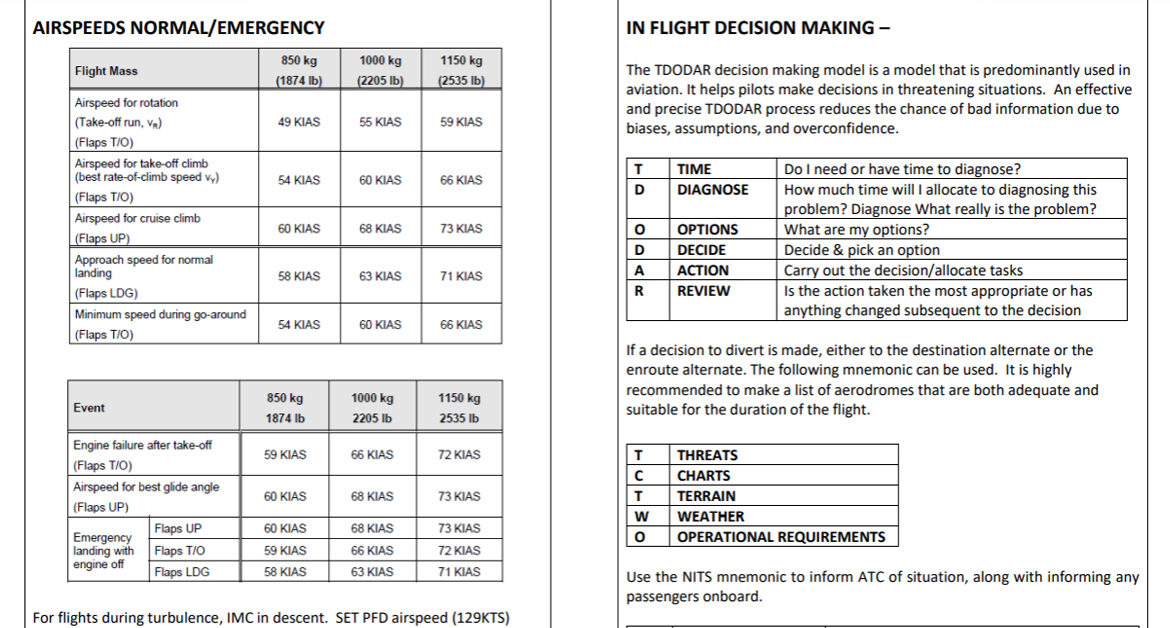

Originally when creating the Normal checklist, I went from the usual book type format which simply follows the aircraft flight manual to a read and do format. I continued this element but slimmed it down and added what was necessary for IFR Airways flights, including a cruise checklist and some notes with aide-memoirs which assist in the briefings.

This became a 2 sided A4 laminate and was very handy for my initial IFR flights. Structured into sections of the flight so it was clear which section to refer to, but remained a read-and-do type. I did almost 100 hours with this new checklist, and although it was good – It became clear when I flew a fair bit more, that more work was required.

I went through various additions and added in little changes as time went on and this ended with Version 1.2B – this would remain for future reference or another fellow IR pilot wishing to learn the ropes.

I then created Version A, which would be used for future IFR flights and as of typing is at V1.3A. This was because I was familiar with the aircraft and to ensure error trapping and efficient SOPs, I would have a checklist known as the Challenge & Response type.

This is usually used in a dual-cockpit environment – but with my experience level on the aircraft and a lot of the actions performed with “Checklist B” were done by memory, I found it seemingly unproductive and the whole point of SOPs is to reduce workload down to a bearable amount.

I focussed on what was “Safety Critical” and what items I probably went over more than once, I removed and consolidated. It then meant I’d follow a cockpit flow, which was easy to follow and then I’d don the checklist and check the items had been completed thus error checking.

This means the difference between the former checklist and the new checklist format is I would no longer do the checklist as I action the items. I would now complete the items, then check that I’d done them and thus ensure that I’d done them correctly and had a way of error checking that I’d done them. The single-sided A4 format was easier to navigate than the double-sided A4 format which was also smaller in text to fit all the items, thus prone to misreading or missing items.

On the reverse of the checklist, I included an AIDE-MEMOIR for the most important aspects in regards to the engine, which is as per the AFM (Aircraft Flight Manual), because there are aspects whereby you would need to shut the engine down to protect it. I also included the preliminary cockpit preparation and external preparation checks as these items are also verified in the NORMAL checklist.

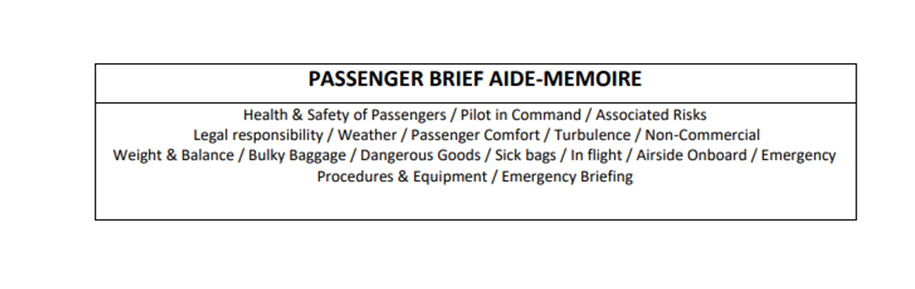

The latest update V1.3A includes the AIDE-MEMOIR for the pre-flight interactive briefing conducted with passengers or as a self briefing for the pilot, an example screenshot of which is attached further below.

CAP708: Guidance on the Design, Presentation and Use of Electronic Checklists

Whilst CAP708 refers to electronic checklists, the principles of design remain the same for paper (laminated) checklists. CAP708 is intended to promote best practices amongst UK aircraft operators with regard to electronic checklists by maximising the potential safety benefits. The material has been developed for the Safety Regulation Group of the UK Civil Aviation Authority by RM Consultants Ltd.

Additional information on how the guidelines were developed can be found in CAA Paper 2000/09 (The Development of Guidance on the Design, Presentation and Use of Electronic Checklists).

This publication complements and should be used in conjunction with CAP 676 (Guidelines for the Design and Presentation of Emergency and Abnormal Checklists) shown below.

Abnormal OPS Checklist

Once I’d completed work on the NORMAL checklist, I began to work on both the ABNORMAL and the Emergency OPS checklists. I did some research and looked at the format of most of these checklists, and realised because they aren’t “NORMAL” you’d normally prefer the READ & DO – because a non-normal procedure pattern performed from memory is not suitable.

Some items are usually from memory, such as airspeeds – but they are included for my peruviol and in a situation where I may have to refer, I can.

The format design from the NORMAL OPS doesn’t change much, it’s categorised into structured sections and for ease of use I designed it in such a way that if the indication on the annunciator panel aluminates amber or the auxiliary displays indicates an amber failure, I know to don the ABNORMAL checklist.

Included are the well-used DODAR process and the NITS MEMONIC which whilst an airline brief for flight crew to cabin crew, can be used to brief the passengers carried but also the same format can be used when informing ATC of the abnormality.

I’ve included a POST-FLIGHT aide-memoire which was also on the normal checklist, as it can be discussed post-flight or if the abnormality is fixed and the flight can continue, it makes sense to go over that aspect of flight whilst the checklist is in hand.

The abnormal checklist is as per the AFM and does not deviate, this is to ensure well-rehearsed procedures from in-flight testing are followed.

Emergency OPS Checklist

Like above, the Emergency OPS checklist follows a similar format and design – but this time it’s in red, because flight safety is at risk, and thus we have a failure that prevents the flight from continuing as normal.

It also matches the annunciator panel indication and the auxiliary displays because a red indication is usually a significant problem.

This does not deviate from the Aircraft Flight Manual and follows the same READ & DO format as any abnormal and emergency checklist should.

CAP 676: Guidelines for the Design and Presentation of Emergency and Abnormal Checklists

CAP676 is intended to promote best practices for aircraft manufacturers, operators, pilots and their trainers in the design and use of emergency and abnormal checklists. It will assist the flight crew in managing and containing abnormal and emergency situations that adversely affect flight safety by providing guidance on human factors and best practices throughout the design process.

QRH

During my training, I used the Pooleys Control board designed for use in Diamond Aircraft. I created a wealth of information to aid in training such as my PLOG. On the ring binder, I had included notes which assist in all phases of flight, including laminated approach charts so I could annotate them based on the weather information – this is in A5 size because that fits perfectly in conjunction with the PLOG that fits on the clips.

But as my IFR flying progressed and became more in-depth and I flew further afield, I decided to develop a QRH – also known as a Quick Reference Handbook. The Quick Reference Handbook (QRH) contains all the procedures applicable for the flight to aid decision-making and to recap takeoff performance and landing performance, including performance data corrections that are also provided for specific conditions.

Whilst the checklist is usually part of the QRH document, these were created separately and I haven’t included that as part of the QRH.

Whilst I am currently redeveloping the QRH as part of the IFR manual, the first design included useful contacts such as all the London Airports, and the contact numbers for watch controllers based at Swanwick along with the contact details for Europe’s SLOT centres. Weight and balance, take-off performance, minima and in-flight performance calculations up to landing.

All of this information will be included in the IFR Manual which will be digitally available on the iPad. Whilst the QRH was developed before the IFR manual, it makes perfect sense that the information is available in both formats for clarity and consistency.

Please note this section will be updated when I have redeveloped this aspect of the framework.

PLOG

My instructor designed a very specific PLOG for the CB-DS in Excel, it includes a space for written or typed flight plans, ETA/ATA, fuel usage, missed approach, weather & ATIS, wind and temperatures at specific altitudes along with frequencies required for the route. I adapted this slightly to include the estimated en-route time, the fuel required, the fuel on board and EOBT, SLOT, AOBT, TOT, LDG and OBT – giving me block hours and air time for both the logbook and technical log.

There was a little space for some notes – so I could monitor the flight and refer back to it as required, this is a big thing for the IR test as you need to re-run the flight. This was ideal for the short flights, but I quickly realised when planning the longer sectors – that I needed more.

I had lots of unusable printable space as the right-hand side of the board was A5, and the lower part was half of that. So I divided what I would have into two sheets.

First sheet – NCO OPS – which would include the flight log, waypoints, MSA, TRK/HDG, ALT/FL, LEG REM, TIME EET and FUEL REM. This would go at the bottom of the board and I could refer to it during the flight or during any electrical shutdown or GPS issue.

As the printout was A4, to the right of that was the A5-sized PLOG which allowed me to record all the details required for the planned flight, such as timings, Airport & ATIS information for departure, including all the frequencies.

Further down I would have ATC clearance information, including the SID, initial level, squawk, frequency for departure, and other information pertinent to the flight, freezing levels and very important taxi instructions especially as I would fly to bigger airports more often.

There was still more space to fit on the A5 so I included a much larger section for notes. A later addition was TZDE, which would give me my stable criteria altitude. The idea is that at TZDE + 1000ft the aircraft would be within a stable configuration and by TDZE + 500ft within specific criteria to be stable, this would be dependent on the weather.

Because most of my flights would be lengthy, they would include high amounts of waypoints and thus I’d create a second printable area with additional route logs. This would allow a carbon copy of the A5 PLOG described above for the arrival airfield.

The second Excel sheet would include the route section in A5, including en route alternates and the weather so I could make a quicker informed decision before any eventuality that is presented. There was still more space so I included FUEL checks and OXYGEN checks to ensure I have that information available when making a decision.

For reference and when inputting data into the GTNs, I have additional printing space for the middle section to include the ATC flight plan route and any NOTAMS of important information that I will need for the flight to complement the flight log.

IFR Manual

I decided that I needed a reference point of information because a lot of the information that I research and use for my flights is separate. The IFR manual will amalgamate all of this into a combined document to assist in pre-flight and increased levels of safety during the flight within an electronic copy on my iPad.

The IFR operations manual will describe the standard operating procedures required for Instrument Rating Training and provide the standardisation required to maintain those skills on a regular and coherent basis.

In this manual, we apply the Standard Operating Procedures (SOP). Under Part NCO the pilot is designated as being in command and charged with the safe conduct of the flight. Pilot-in-command responsibilities and authority under Part-NCO are fairly standard and uncontroversial. In order to fully understand the procedures specified hereafter, pilots must be familiar with the aircraft flight manual (AFM).

The SOPs are complementary procedures and represent a unique philosophy to ensure maximum standards of flight safety in a SEP aircraft.

As of writing, the IFR manual is currently under development.

Flight Briefings

Part of Standard Operating Procedures includes conducting thorough pre-flight preparation and conducting effective briefings. The use of briefings is to understand the desired sequence of events and actions and thus achieve the safety and efficiency benefits of good flight preparation.

The flight preparation phase allows the ability to plan, calculate and develop the flight, and in the case of IFR not limited to; fuel quantity onboard, departure alternate, enroute alternate, destination alternates within NCO, weather forecasts and routing(s) to avoid potential frontal icing or thunderstorms.

Many aviation incidents and accidents can be linked in some way to flaws in flight preparation. Having the correct information available such as enroute weather, Jeppesen charts and aircraft performance will assist in conducting effective briefings.

The first briefing known as the “Pre-Flight Brief” as the sole PF is to self-brief, but to some extent brief the passengers if carried on the flight ahead; most notably in-flight emergency procedures (preparation for emergency situations or evacuation of aircraft) or turbulence, high workload situations and what to do to ensure in-flight safety. It is also a chance to recap the routing and the expected weather that is anticipated, along with a quick glance at the latest actual weather.

An example of the aide-memoir for the pre-flight briefing, now included in the latest checklist.

The second briefing is familiarisation with the anticipated departure, also known as the “Departure Briefing” and thus the conditions that are expected along with the plan, the get-out plan and the serviceability of the aircraft. It’s also a chance to brief the taxi routing from the stand to the runway and discuss any hotspots that could hinder safety. This would usually only take place once an IFR clearance has been received and a departure route has been given.

An aide memoir is on the checklist and can be used to develop the briefing before take-off. This goes over performance, noise abatement procedures and rejected take-off or EFATO’ or any stop-or-go decision including returning to base or diverting to the departure alternate. This briefing should be dynamic based on the conditions or the challenges expected at the departure airfield

The third briefing is the “take-off briefing”, and is also a great opportunity to error trap the departure route including a gross error check of the navigation display on the PFD/MFD; which could have many key threats such as terrain or adverse weather (Thunderstorms or TCu) and a recap of the performance figures.

All these briefings are conducted during low-workload periods, outside the aircraft, on the stand before the taxi and at the runway hold after the power checks have been completed. Whilst these briefs are usually conducted in a two-crew format, doing this out aloud to yourself or your passengers who could be vanilla PPLs or frequent flyers builds confidence in not only your ability but for those watching with envy at your professionalism.

The briefings themselves should be based on the logical sequence of flight phases, and in flight, the fourth briefing is the “approach brief” which if done in a timely manner is a recap of the expected approach to the arrival airfield. Usually, this takes place once the runway is confirmed, however, it’s good practice to prepare for the arrival and landing during the enroute phase with a detailed look at the approach chart for the expected runway in question.

From my experience, the runway can change before departure, whilst en route then again whilst on approach – especially at busy international airports sensitive to noise, like major European cities. Similar to the departure brief, it covers performance, navigational requirements and threats and mitigating those risks.

Once the aircraft has landed, it’s always good practice to post-de-brief any elements and if necessary make adjustments for future reference by note-taking and discussing these items with a flight instructor or suitably qualified pilot.

Call-outs

In the commercial world, callouts are used to provide clear and precise communication among crew members and are essential for maintaining situational awareness and maximising the safety of flight. They are usually used to give a command, delegate a task, acknowledge a command, initiate or complete the transfer of information, ask a question, call out a change of indication, identify a specific event, etc.

I’ve looked at ways of implementing these callouts to acknowledge a command, such as a change of altitude, approaching an altitude or a simple way of checking that I’ve completed a task and to boost situational awareness within the single pilot IFR environment.

It’s a sure good way of verifying that you have taken the correct action. Then if unsure, it’s a call-to-action a resolution to any problem and thus an error trap.

A great example is when the KAP140 announces “Altitude” – I would respond with “1000ft to go” to acknowledge we are approaching the level cleared to. This is a great way of boosting situational awareness.

Working on SOPs

During Autumn 2022 I decided to work on some procedures and test them with a fellow IFR pilot. I flew the aircraft to Belgium and back, to further improve what I developed over the Summer.

Part 1 of 2 – The start of working on set standard operating procedures in the challenging IFR single pilot environment in the Diamond DA40. Brushing up and improving the process of briefings and callouts to boost situational awareness. Join us as we fly the aircraft to Oostende-Brugge International Airport from London, for a first-time visit on only my 3rd attempt. We conduct an ILS Approach into Runway 26 at EBOS.

Part 2 of 2 – A continuation of set standard operating procedures in the challenging IFR single pilot environment in the Diamond DA40. Brushing up and improving the process of briefings and callouts to boost situational awareness. Join us as we fly the aircraft from Oostende-Brugge International Airport to London, as we work on the SOPs at a larger airport. We conduct an Instrument Departure from Runway 26 at EBOS.

Looking at perfection

In the world of IFR flying, you have no choice but to be a perfectionist; you have to fly to precision and ensure flight safety in some of the most adverse conditions in the atmosphere. However, 90% of the time, for 90% of the flight you’ll be in clear skies – or VMC; also known as visual meteorological conditions, but on the other hand 10% of the time, for 10% of the flight you may encounter some of the most challenging conditions to fly an aircraft in and you have to do so at the same high standards.

This is why I have taken gaining the IR so seriously and have developed set procedures using all the available information, removing any confusion, or bias and improving clarity – thus for the great majority of the time my standards will not slip.

Some say perfectionism is bad, but ensuring having the correct tools at your disposal and having solutions to the scenarios you could face in a single-engine aeroplane in an IFR flight isn’t a bad thing.

In airlines, with two or even three crew this process is used day in and day out and air travel is only as safe as the operator, the equipment, and the training procedures that underlie the flight itself. Pilot error is thought to account for 53% of aircraft accidents, with mechanical failure (21%) and weather conditions (11%) following behind.

There’s no doubt that using full-fledged SOPs frequented in the airline industry to spread the benefits of this operating philosophy to everyone in the system, especially the grassroots is of great advantage.

Safety Benefits

The NTSB said it best in its statements on the role of SOPs in flight safety: “Well-designed cockpit procedures are an effective countermeasure against operational errors, and disciplined compliance with SOPs, including strict cockpit discipline, provides the basis for effective crew coordination and performance.”

SOPs are globally proven to aid decision-making and clear procedures for carrying out the resulting actions. Compared with commercial ops, callouts and flows are uncommon in piston-GA operations, which rely heavily on the manufacturers’ written do-lists. and that’s why those who don’t use SOPs often make bad decisions or inconsistent decisions, picking up bad habits and showing great deficiency during emergency operations.

SOPs contribute to preventing or mitigating crew errors by strict adherence to SOPs, including running routine checklists. Managing operational threats and anticipating or managing threats, thereby improving the safety of the flight. Enhancing understanding and adherence prevents misunderstandings common to many accidents.

Another benefit of SOPs is that they serve as effective indicators of where more training is needed. A great time to self-learn procedures, or some recurrency work with a flight instructor.

Outcome & Disclaimer

The outcome is the simplicity of flying IFR, whilst maintaining the highest of standards for many journeys to come – creating consistency and a decrease in the amount of errors made. In the example video below; I put to good use SOPs such as briefings and callouts as described in more detail above.

There is more to come with an updated version of the QRH and the implementation of an IFR flight manual to assist me in my adventures. So check back in the future for a more in-depth update that will improve my flying.

The information provided on this blog is free of charge and for informational/educational purposes only. You accept full responsibility for its use. I will not be held responsible for any errors or omissions, or for the consequences resulting from the use of this information; or use in flight without the prior advice of a qualified flight instructor.

I am not a flight instructor, so please ensure when writing your very own SOPs that you speak to a flight instructor and seek their advice before embarking on your very own AltMoC project.

Version 1.1 – Last Updated 23/03/2024

Aircraft –

The aircraft is a DA40 TDI, which uses a Thielert “Centurion” 135 hp (101 kW) diesel engine and burns diesel or jet fuel. It has a constant-speed propeller and FADEC (single lever) engine control. G-ZANY is based at Stapleford Aerodrome, Essex, UK and was delivered as new in 2003.

Read more about the aircraft on the dedicated page

Supporting the YouTube Channel –

Support the YouTube Channel –

Welcome to The FLYING VLOG…

I am a current PPL(A), SEP (LAND), IR(A) SE/SP PBN, IR(R) & Night holder. Flying the world, exploring its hidden treasures. Taking pictures and vlogging the journey; I hope I can provide you with an oversight of my progression as I develop my skillset and airmanship in exclusive videos on my YouTube channel.

Now flying IFR in the Airways of Europe & beyond. Bringing you an exclusive niche to YouTube, flying in the same skies with commercial airliners.