The IFR Journey

Introduction –

My goal has always been to become a fully-fledged airline pilot. Unfortunately, I don’t have £120k, and many obstacles have got in the way in the last few years that have prevented reaching that goal through a modular route. With the impact of COVID-19, this dream now seems even harder to achieve.

In 2015, some 4 years after I got my Private Pilot’s Licence, I added the IMC Rating. It is a very useful alternative to the full Instrument Rating; however, it is not normally recognised outside the UK, but a lot simpler to obtain than the “full” IR. The course consists of a minimum of 15 hours, all dual instruction, with a written examination and a skill test.

The privileges of the IMC rating allow you to fly a UK-registered airplane in UK airspace classes D, E, F, and G, in IMC, out of sight of the surface. You may also carry out Instrument Approach Procedures to published Decision Height or Minimum Descent Height and to undertake missed approach procedures, with a minimum take-off and landing visibility of 1800m. The rating is valid for a period of 25 months, after which it is renewed or revalidated by flight test.

Ever since that challenging flight back from France in 2018, I’ve really wanted to get the full Instrument Rating. Not only would my flight back have taken place the day before, thus saving me a further night stranded in France, but it would have meant a much pleasant experience for all on-board, although that is somewhat debatable.

The Instrument Rating (IR) allows private pilots to fly in the cloud, in any class of airspace, including airways, and for you to fly a Category I ILS descent to a decision height of 200ft and RVR of 550m (2 crew) or 800m (single pilot). Because of my history of instrument flying, I can take the competency-based modular “CBIR” route, which is designed to tailor to my specific needs to get me up to the standard required to pass the initial IR flight test.

It still means I had to undertake some ground school at an approved ATO and pass the following theoretical knowledge examinations; Air Law, Aircraft General Knowledge – Instrumentation, Flight Planning and Monitoring, Human Performance, Meteorology, Radio Navigation & Communications.

ATO Theory & FCL Exams –

Most of spring 2019 was spent researching ATO schools for the theory. I came up with a shortlist that included Bristol Ground School, CAPT, or CATS Aviation Training. These were the only schools approved for such courses. After many recommendations, I decided to complete the ATO theory with Caledonian Pilot School, which would take place at White Waltham or Prestwick.

Sadly there were no dates down in the south of the UK and I wanted to complete the classroom-based phase before moving to a new job in the autumn, so I went ahead and booked the face-to-face tuition up in Scotland. The training materials provided are PDF books, after which you are supposed to do the progress tests. You can’t take the exams before you have done the reading, the progress tests, the time in the classroom, and then the mock exams so as much as you put in, you get back out, and with a full-time job, it’s not an easy feat. EASA requires that 10% of the total study time for each course must be done in an approved classroom.

The total cost for the course including the ground school and electronic materials cost £595.00.

In order to complete the examinations with the Civil Aviation Authority, you must complete the required time in the classroom, the progress tests and then the mock exams, which are suitably provided by CAPT.

The training materials provided are PDF books, which requires many hundreds of hours of detailed reading with a full-time job, it’s not an easy feat. Sadly, there were no dates down in the south of the UK and I wanted to complete the classroom-based phase before moving to a new job in the autumn, so I went ahead and booked the face-to-face tuition up in Scotland.

I booked a coach with National Express costing a total of £32.20, this was versus a total of £200 for a flight with easyJet or a direct train journey.

Additionally I needed one night’s stay in a hotel, this cost a further £100 in central Glasgow.

The fees do NOT cover accommodation, exam fees, lunch (although they do provide coffee and biscuits), the Jeppesen Student Pilot Manual, and the flight computer required for the Navigation and Flight Planning exams. All these things are required for the theory and the exams.

I had considered flying light GA up to Scotland, however, the weather on the way would have been atrocious. It was CAVOK in London, cloudy on the M1, showers of rain in Birmingham, torrential rain in Cumbria, and a deluge in Glasgow.

I elected to stay in the Hotel Ibis Glasgow City hotel overnight and had a lovely meal in Wetherspoons after 10 hours of a numb backside on a coach along the spine of the country. With not much time for sightseeing having never been to Glasgow the following morning was an early start and I travelled the short journey to Prestwick for the theory. I was joined by only two other students, one taking a CPL (H) and the other a CB-IR; which is all pretty much the same thing. We were given a lift to the nearby Morrisons for lunch, where unfortunately the café was closed. So I opted for the heated for hours on end option. The day went very quickly but it gives you the required time to participate in the practical flying element and satisfy the rules set out by EASA.

After a long day, I met up with an old friend from BA and had food in Wetherspoons (again) before the 10-hour overnight coach journey to London. This was my least favourite experience, as by the time I got to Lockerbie I already had a numb backside.

I arrived back in London with good news – I would be starting a new job. However, after re-reading the CAPT theory notes twice – I still hadn’t found the time to start the exams. This was an excruciating time because I was raring to go, but I was on training and couldn’t find the time to go take the exams at Gatwick. This delayed my progress by some 5 months and at this point, I was becoming very frustrated. I started the examinations in late February 2020, first passing human performance, quickly followed by Air Law. Surprisingly I had a very difficult exam with Aircraft General Knowledge and failed, but I have to blame my lack of preparation for that.

However, to no surprise, I passed IFR communications and re-took Instrumentation a week later and gained a pass. I spoke to the examination team and based on their comments, the rumours on Twitter, and the front page of most newspapers I didn’t make any more exam bookings. Little did any of us know what was brewing before our very eyes around the world….

040 Human Performance (40EIR) – Passed

010 Air Law (10EIR) – Passed

092 IFR Communications (92EIR) – Passed

022 Aircraft General Knowledge – Instrumentation (22EIR) – Passed

COVID-19 & inevitable delays –

It was originally hoped that in summer 2020 I would complete the practical elements and the IR skills test. Adding to the delays of lockdowns and the closure of the examination centres, the aircraft I was going to use was having a complete avionics overhaul in Belgium and with an ARC expiring and COVID ravaging the globe, things didn’t look like they’d be progressing any time soon.

The new avionics upgrade meant many hours would be spent learning and perfecting the new systems before finally undertaking the practical flight training. I spent the latter stages of summer and most of the autumn learning and perfecting the new setup. More on that in a moment.

Once exams restarted, I got back to studying. Unfortunately, I misunderstood how demanding the final exams were. It must have been the COVID causing brain fog because for whatever reason I just couldn’t pass them. It is what it is, and it is very embarrassing having stormed through all the exams earlier on in 2020 without any major hiccup bar one exam. Being extremely keen, I rebooked the exams later in August and yet again missed out on a Pass. I was becoming extremely anxious about the whole thing and probably why I failed them.

I turned to the training school before my final attempts. They provided me with someone who could provide additional tuition. This additional tuition set me back a fair amount in costs but provided me with the knowledge to get some of the highest pass marks of all the exams I had taken. I was extremely happy and, despite a second lockdown (albeit the CAA was continuing examinations under the guise they were an educational institution), I now had closure and was relieved that I’d passed the theoretical knowledge part of the course.

Then came Tier 4 restrictions for England, and the rest is history. COVID really prolonged an already deferred start to my IR and the whole situation made me feel as if I’d never get there. Lockdown 3 came along and my Nan who was in hospital sadly got COVID and passed away. It really was one thing after another. I knew based on the first national lockdown that it wouldn’t be until at least April that I would be flying again. Then of course you’re at the mercy of the weather that that would end up plaguing my progress.

Before the lockdown, I renewed my IMC, in the hope I could use the rating to gain some more experience before undertaking the IR training. My flights were sporadic in nature and only when it was allowed could I fly again, and this further increased my frustrations of what was becoming a pain in the backside to gain an instrument rating.

050 Meteorology (50EIR) – Passed

062 Radio Navigation (62EIR) – Passed

033 Flight Planning and Monitoring (33EIR) – Passed

GTN XI Training & Sim work (Flight Sim) –

The aircraft I would use for my training was the aircraft that I currently have a non-equity share in which returned from Belgium in Summer 2020 with a significant upgrade to its avionics suite. The aircraft now sported an impressive IFR spec with twin Garmin GTN 650 XI and Aspen EFX 2000 PRO Max units.

During the quieter winter months of reduced working schedule and lockdowns, I downloaded the Garmin GTN Xi Trainer. This explores the features, options, and fundamental operational aspects of the Garmin avionics. When used with the GTN Xi Series Pilot’s Guide, it’s an effective way to improve avionics familiarity and proficiency.

Additionally, I spent many hours reading the ASPEN manuals to enhance my knowledge and understanding of the technology and how to operate it. EFIS requires training with an instructor, and at first, at a glance is very daunting before you actually get used to the systems. Unfortunately, there isn’t a similar setup for the ASPENS although you can invest a significant amount of money into upgrading the many SEP aircraft add-ons with a Garmin XI and ASPEN PRO MAX in the flight simulator.

Unless it’s a commercial aircraft I can’t get used to the idea of using Flight Sim at home to enhance my procedures, so very sparingly over the course of my training did I use the flight sim, if at all. Before I started my IR, I used to regularly fly the Flight Sim Labs Airbus A320 which provides a very detailed IFR airliner system. It just doesn’t give the feeling and sensations of a light aircraft, although a highly valuable tool to perfect and learn the tricks of the trade, in combination with the online virtual network VATSIM.

Start of IR Training (PRE-ATO) –

It was now April 2021 and the first area we would cover on what would be the official start of the IR training was VOR tracking. This was in some way the bread and butter of what I would use to navigate around with, so it was somewhat important. This was a key area I struggled with in the examinations, but as I found out it was mostly the presentation of the VOR and not the theoretical understanding of how they worked that I struggled on in the ATO theory.

The first flight was a fairly short sortie out via BRAIN tracking LAM VOR and then towards CLN of which is the first three waypoints of the routing for the IR training. After fogging my brain and confusing me whilst my workload was still relatively low, I successfully navigated to and from CLN via BRAIN using the VORs – I was then given vectors away by the IRI and told to identify where we were position wise. This was the basics, but with new instrumentation, it wasn’t hard to forget how things work. A short 1hr 10 minutes in the air and a safe return to Stapleford ensued.

With attempts to block book my lessons, the very next day we went to the nearest NDB station and completed an hour’s worth of NDB tracking and holding. We left the NDB to hold various times and I was told to identify what entry we would need to re-enter the hold. This was fairly fun because it really started to challenge my brain.

The weather provided an interesting perspective, with lots of challenging turbulence to add into the mix and at the low levels, we were flying it wasn’t very fun, especially as I hadn’t flown much IFR at the time.

In April, we flew again. This time some more holding at the local NDB was undertaken. I’d have 135knots groundspeed on the outbound leg and 90 knots on the inbound leg and this was all due to the upper winds being very strong, which was intentional as it would mean I would further appreciate why some conditions aren’t practical not only for holding practice but also when flying IFR in general. This was super hard work and it wasn’t really ideal training conditions being such a newbie. The IRI took this into account and decided that we pretty much covered that area to death and would be covering it on the full sorties at every flight, so I appreciated the NDB more so after this.

This was a rather long flight and didn’t just cover some instrument basics. It was the dreaded stalls, unusual attitudes, and partial panel training. It’s this sort of stuff I don’t really like, but I think it trains you to avoid these killers and, in my case, never go near them – but you just never know when you’ll inadvertently place yourself in that situation.

To start off, we flew as slow as we could with power off and try to maintain the altitude as much as practically possible to induce a full stall so I could see what it was like. We went all the way to the buffet and then recovered. The IR training only requires stalls to the first sign of a stall (stall warner) but as you’ll all know from my YouTube videos, the DA40 stall warner chirps off very early and way before any stall could be entered, let alone a full stall. So it was good to cover the basics of flying the DA40, but the only difference with this training was I could do so under the view obstructing devices (Hood). We did a stall in the turn under the hood and then went to a partial panel for the rest of the sortie.

For partial panel exercises in a glass cockpit aircraft like this, the brightness of the panel is turned all the way down to zero, so you cannot see any information on the screens. It’s important to remember how to turn this back on as I found out in a later lesson. We climbed up towards the coast and the IRI comments on the perfect amount of right rudder that I had for this climb. I could see a little through my peripheral vision and detected that we are in IMC and I believe this was the game-changer for what happened next.

I kept turning left, and despite the IRI asking why I was turning left, I looked down at my instruments and I still thought I was straight and level. Oh my god! It’s the leans. I’ve never experienced anything like it. WOW! If you’re going to experience it just the once, it was a good job I had a qualified professional sitting in the right-hand seat rather than yourself with a few passengers.

Some more VOR tracking back to Stapleford was carried out and after 1 hour 45 minutes of rollercoaster fun, we finished for April.

We were now into May and I was hoping to start making some serious progress, however, as I expected, the weather was unseasonably bad. Upper winds were 45 knots across the Southend Hold and forecast to get worse as the day went on, with heavy driving rain within the fronts. Anyone would think it was a Bank Holiday Monday, it was….

A few days later we had two flights booked, so I was happy that we would be catching up potentially with lost training time. The first flight was a very short flight to recap on stalls and unusual attitudes; this was rather rewarding because after the previous flight where I really lost touch of my senses and ended up in a situation one really doesn’t want to put oneself in. This was nice to quickly recap before revisiting on later sorties.

The second flight was another sub-airway routing and tracking the VOR to BRAIN. Once we reached BRAIN I would track CLN VOR and it wasn’t Auto Identifying. This was clearly an issue as I obviously hadn’t checked the NOTAMs to see if it was unserviceable or not. I then proceeded with GPS instead of tracking the VOR, it’s at this point I went climbing without asking ATC (I was on a traffic service – and this requires you to request the altitude change from ATC).

The IRI was quick to remind me and put an abrupt stop to climb. Not something you’d want to do in Class A airspace, so a very important lesson, thankfully it was Class G, but that’s not the point. At this point Southend ATC clarified my intentions for training, we were running a little bit late – so their next instruction should have been followed.

We requested to route CLN direct GEGMU then SND as per the PLOG. However tracking towards GEGMU they told me to route direct SND, cleared through controlled airspace at 3000ft. I decided to continue to GEGMU. But this was what confused me. They did ask our intentions, and I would have assumed we’d follow them. To then give a clearance that was different to the request was what really confused me. But it was an instruction and I should have followed it or at the very least queried it.

As we were en-route to SND the IRI queried what hold entry I would fly. I was already getting flustered so it was a perfect time for the IRI to check my knowledge. If only I had done a better job of the pre-flight preparation I would have realised and I would have been able to have given a reasonable answer in a justified manner.

We flew our entry and flew back to the NDB to start holding. I think at this point I was getting tired, and I kept forgetting to set the timer when abeam the NDB on the outbound track. This is a really important part of the holding procedure as it allows you to stay within the protected area of the hold and gives you a fighting chance of turning to intercept the inbound heading fairly seamlessly without being too wide or too narrow.

It was now time to fly the ILS. We flew away from the beacon as per the procedure and I quickly dropped to 2000ft, which is the minimum altitude you should be at until you capture the glide path successfully. This was very poor because multiple times I dropped the altitude. This would be an instant fail. The reason? Trim. Trim Trim! Like in PPL flying, this was critical to reduce workload especially in IMC (or mock IMC), and would have been my friend in this situation, especially where I lowered power to ensure I wasn’t too fast.

The approach was riddled with errors including being outside of limits and carrying too much speed. I’ve flown better and I was disappointed in myself. I hadn’t flown many ILS approaches over the last few months, so I was fairly rusty. The go-around was poor, I didn’t kick the ball in the middle during the climb which meant with the winds we had, I was drifting away from the runway heading. We flew the missed approach instructions given to us by Director and were re-vectored for another ILS. This again was outside of limits and too fast compared to what I should have flown. Maybe it really was time to call it a day today as I was getting exhausted, so we flew back to LAM and landed at Stapleford after a very busy but rewarding day of flying.

I got home and in the week that followed, I gave the NOTAMS a good read and realised that CLN wasn’t unserviceable, so this was unusual that LAM was identifying correctly but CLN wasn’t. I changed some of my checklists and made them clearer so that I could ensure my flights would flow more smoothly and I would have all the information to me in flight and could provide the most comfortable experience for me.

Today we would fly two flights, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. The winds forecast would be above what you would fly an NDB hold (25 knots) and increasing as the day went on. (Max 20 knots for the test). It was almost June, so what on earth was our weather playing at. 35kt gusts were appearing in the evening so we had to ensure everything was conducted in a timely manner. Therefore, we promptly departed for Southend, this time sub-airways in order to get the sortie completed.

As all my previous departures had taken place in relatively light winds, I didn’t adjust my departure track to capture the track away from LAM to reach BRAIN, so rather than capturing the track within 3 miles, it was a little later than I’d anticipated. This is important because we could easily be blown either into the circuit and the Stapleford ATZ on departing or be blown away from capturing the track to BRAIN in a reasonable amount of time, so another professional way of doing things would be to wind correct the headings used for departure. It’s the minor details that really matter.

We climbed up towards BRAIN and then on tracking from BRAIN to CLN we realised yet again that we couldn’t auto-ID CLN. We listened to the DME and that was working (Heathrow ATIS). I found it interesting as to why it wouldn’t identify – perhaps signal quality? We continued using GPS and tracked from CLN to GEGMU. This time I requested the climb from ATC so, so far so good.

Routing towards GEGMU we were given DCT SND at 3000ft and cleared to enter controlled airspace. I perfectly tracked SND all the way. My prior planning allowed me to identify the correct hold entry. On flying the entry to the hold, I quickly realised how strong the winds were and before I knew it we were flying the outbound leg. One thing I have realised about Southend is you can get two different wind velocities at different parts of the hold, and this is simply because of the sea breeze effect and that the airport is near the coast.

We flew one hold perfectly, and then the IRI said “right now let’s fly the procedure.” I remembered my previous errors and tried not to bust my platform altitude and correctly control my speed and attitude as I flew out towards the turn. I realised though as I turned to intercept the ILS, the wind would push me away from the localizer. I should really have pre-empted this or at the very least annotated my laminated chart so that in the future I can intercept more cleanly. With the strong winds, I was working hard but the approach was much better than the previous flight(s) and I flew a perfect ILS all the way down to 240ft (Decision Altitude).

The instructor cancelled the vectored ILS and we flew direct LAM for a sporty landing on Runway 21 at Stapleford, just in time for a spot of lunch whilst the next student took the aircraft to Lydd. I realised during the break that the weather wasn’t ideal to continue training. The PROB30 in the TAF had come true and already we had some decent showers popping up.

I really thought we would cancel, but gone were those days of cancelling on a whim! The next student before my next flight flew the aircraft to Lydd and he reported some fun flying conditions, IMC, and lots of turbulence inside the weather. Using my new Golze tool I tracked the student’s routing through the weather towards Lydd. I am not a fan of turbulence so sat rather uncomfortably whilst watching the rain showers pass through and saying the obvious – “I’d rather be on the ground than in the air wishing I was on the ground.”

It had cleared up substantially for my flight, and I had planned the stronger winds in flight and the fact I would be flying the ABEAM HOLD at ROMTI after the RNP. This was something to tick off the box, as it’s very rare we would have to fly this, but at least I could say I had flown it.

I failed to do a RAIM check on the ground, but a quick recap of the brilliant GARMIN GTN 650 XI means you can also do this in the air and set it up so that with your flight plan in the box, you can have a RAIM calculated for your approach time. This is great for the longer distance journeys where you might use a bit of that 5% CON and would need to make much more informed decisions en route to ensure a safe flight.

I also learned a few other things with the GTN system, that would help and assist me on all future flights. This was a steep learning curve but I enjoyed expanding my knowledge and receiving and interpreting the wealth of information and data that it throws your way. It’s all RAW data so it’s the very pinnacle of IFR flying.

As I flew the RNP, the instructor asked me to clarify what altitude I should be at as per the chart. We were well above this, but I was flying the advisory glide path and that wasn’t correct for this approach – a lesson learned there. I should’ve followed the check altitudes and cross-referenced with the chart on the way down, as it meant initially I was outside of limits for the RNP.

We flew towards the BEMLA waypoint and did fly a few laps of the ROMTI hold using GPS. It’s here I learned that putting D Flight mode on the bottom GPS would be highly beneficial to my flying and thus improves my situational awareness throughout. It was time to fly home and as we navigated back to Stapleford, I heard the good news that on my next flight I would be going to fly in the Airways and would now need to file Flight Plans for all future flights as they would be true IFR.

Things would slowly start coming together now, and maybe I’d have the IR in the bag for use for most of the summer. The weather forecast was starting to improve, however on the day of the planned airways flight with the flight plan filed and the majority of the planning done, the IRI had to cancel due to a sickness bug. The dream of flying with passenger airliners in Class A had to wait a little longer…

Further Delays & Airways –

As we progressed into June, the weather was still changeable. An overnight MCS system moved up through France and sat over East Anglia and our routing. Whilst probably flyable, there were some embedded CBs, risk of icing at 9000ft, and low cloud that caught many out that morning. I used the recently acquired Golze to make an informed decision that my first airways flight was probably best not to be flown in this flying environment, what was most frustrating was this wasn’t really forecast at least not for the whole day.

It was now into the second week of June and the opportunity presented itself for two IFR airways flights that day – one in the morning and one later that day. I had filed the flight plans at home using AFPEX and when we got a little behind schedule I realised how accurate and how much time you need to have before your EOBT to depart on time. I can only imagine doing this pre-COVID and having to endure a penalising slot if we missed our EOBT and CTOT.

We departed Stapleford via our planned routing to intercept the 062 radial from LAM and contacted London Control as planned. They initially told us to remain outside controlled airspace, before shortly climbing us up in steps towards BRAIN, our waypoint for our initial airways join. Within moments we were under a radar-controlled service and once we climbed above the inversion, the controls felt very different. It was as if flying in Class A airspace changed the entire dynamics of flight. On reaching FL90 I had a sneaky look outside and enjoyed the view before getting busy as shortly there were multiple handovers to London Control, Thames Radar, and Southend Director. You barely had time to think, let alone write the ATIS down.

The next phase of the flight was multiple descents and a direct routing to SND. However, on this occasion, we were vectored to the north of the airport to allow for a departure. I thought this was rather strange, but I guess they would have climbed into our path. I flew a couple of NDB holds, and two procedural ILSs before the short hop back to Stapleford for some lunch.

On the second flight of the day, I flew out of Stapleford for the same airways routing, but this time we were going to Lydd for an RNP approach after we had completed our task at Southend. The climb rate was noticeably slower as we were flying at the hottest part of the day (due to the diurnal heating effect), so I pitched back to 70 knots to maintain a decent climb rate into controlled airspace and London ATC gave us a climb all the way up to FL90. This time it was a bit different with a radar heading given before being allowed to resume own navigation to CLN.

Once again time had passed so quickly and we were already starting our descent into Southend, but I had to laugh as Thames Radar had given us no ATC speed restriction; we both laughed, and I informed them we were a DA40 (how fast could we go???)! We flew a perfect CDA with a descent rate of 1000fpm and established directly for the ILS. This was much bumpier than the morning, but it was inch-perfect and within limits all the way down. Following this, we flew our planned routing to Lydd avoiding the gliding site at Challock. At this point, I was becoming exhausted, and the heat was unbearable when cruising at the lower levels due to the higher OAT. The RNP into Lydd wasn’t perfect so I noted that I needed to do some work there. We flew the missed approach to BEMLA which then routes you around to ROMTI where you start your hold. Confusing? I know, the whole thing has a dedicated forum on the PPL/IR Europe website.

We decided to route back to Stapleford VFR and enjoy the view as well as giving my brain a bit of a rest. It was now time to come up with a plan, and for me to decide on the routing to Cambridge before brushing up any final bits before conducting an assessment flight with Stapleford for the ATO phase.

The routing to Southend was straightforward and I saw the planned routing on CFMU that most training flights from Stapleford to Southend use. I hadn’t seen the routing to Cambridge, and a quick check of the UK SRD (Standard Routes Document) found nothing from Stapleford to Cambridge. However, a quick look at London City took us from CLN to Cambridge via ABBOT. So I constructed our usual route to CLN via BRAIN and added the direct to CBG via ABBOT and the system accepted this route.

The initial plan was to route airways, fly an ILS at Cambridge after a few holds then fly an RNP before returning to Stapleford. The instructor had booked the approaches with ATC and all I had to do was file the flight plan. I had a good look at the NOTAMS and unfortunately due to work in progress the ILS was unserviceable till early-mid July. You just couldn’t make it up!

So far, my progress had been thwarted by COVID, weather, ATC closures, and now equipment maintenance. As I type this, you can imagine the frustration that was boiling inside me. My pre-flight discussions and briefings consisted of the weather but increasingly was having to discuss equipment unserviceability or reduced operating hours. This was becoming an effort and my patience was forever being tested and continued throughout my IR training.

I consulted the instructor and elected to fly the NDB approach after a few NDB holds. The heat was extreme and so was the humidity. I wore shorts because today was exceptional. I wasn’t complaining by any margin as it was a perfect day for flying. We departed Stapleford and were quickly given a climb up to FL90. The enroute phase for this training sortie was a little bit longer than usual flights to Southend or Lydd. I had anticipated a shortcut by ATC but didn’t expect to be handed over to Essex Radar. It made sense though with Stansted in the distance and us shooting across one of their stack levels. We began our descent and were given a procedural service by Cambridge and already I was missing the clearer air. The turbulence and heat in the lower levels made for a challenging day out here. One moment it was smooth, then as we flew to the other side of the hold we were thrown about and had to re-trim the aircraft and then correct my heading and or altitude. This happened multiple times around the hold as the daytime heat increased.

The NDB approach wasn’t perfect and neither was the RNP. However, this was simply a minor blip in the road to the ATO phase and we discussed the many pointers that I would probably need to demonstrate to the ATO on their assessments. We awaited the response from the ATO on what the next steps were.

Originally a plan to fly airways via Southend had to be scrapped due to a controller shortage and while I fully understood the world we live in now, things outside of my control were changing day-by-day. I was beginning to think these bumps in the road would be never-ending.

We managed to find an alternative plan, and so the day before the ATO assessment we practiced a DME ARC and ILS into Lydd. The weather continued to frustrate – low cloud, mist, patches of fog, and embedded CBs and TSRA were all present. The result was lots of drinking tea & coffee and waiting for a break in the weather. It felt like mid-November rather than mid-summer, but it eventually cleared, and we flew our departure remaining outside of controlled airspace to Lydd, passing through the layer of clouds before eventually sitting on top of them for our enroute section to Lydd. I planned meticulously so that I could intercept the DME ARC using VLOC from GPS mode. This was very successful and it’s a shame that the ILS wasn’t as good as my previous one. Maybe it was my frustrations and I needed to just look at the bigger picture and concentrate that little bit more?

We flew the missed approach, and our intentions were to intercept the hold. However, I noticed out of my peripheral vision a huge TCU over the hold. The increased in prominence and it looked extremely powerful. It quickly towered over us and started to develop an anvil. We routed away from this and flew towards Stapleford via the Southend CTA where I flew the cloud break procedure into Stapleford. A quick look of the Met Office app showed these cells that formed on a convergence line north of the coast and subsequently became thunderstorms as they tracked towards the Solent region. It was a good decision to avoid that weather system.

ATO Phase –

The day of the assessment came along, and the weather again continued to frustrate. I was handed the aircraft over from a previous lesson and taxied over to the clubhouse where I met the senior instructor who’d oversee the assessment. This was to check I could achieve test standards in the 10 hours prescribed with the ATO.

There was a weather front sitting on the route between ourselves and Lydd. The rainfall looked somewhat heavy but didn’t look outrageous that it would not permit our ability to conduct a safe flight. The wind made my planned intercept of the radial from the LAM VOR very aggressive, so some work was probably required there. I had pre-phoned Lydd as the previous flight reported they were flying Runway 03 which meant we couldn’t fly the ARC. Thankfully the rather kind controller informed me there are local procedures in place to allow an approach on Runway 21 whilst the active is Runway 03. We continued our flight towards Lydd and entered very thick IMC, with rain completely reducing visibility to zero. The weather was just sitting on the downs and the turbulence was, fortunately, negligible.

We continued our routing towards intercepting the DME ARC. I completed all my checks and set the aircraft up in a timely but efficient manner. With a 25-knot tailwind, we quickly flew the ARC and had a 142-knot groundspeed readout as we established on the ILS. I had to use far less power than I’ve ever done before to maintain my 90 knots IAS and an increased descent rate towards the decision altitude because of the higher than usual groundspeed.

This ILS was as good as the ones I had done almost a month ago and it was well within the prescribed limits. I was happy and so seemed the senior instructor. We flew the missed approach and then flew back to Stapleford again through the weather we’d just flown through and back via the Southend CTA for a visual approach into Stapleford. He gave me a few pointers, but these were relatively minor in nature. I was on my way to the ATO phase.

Once again, the British summer weather never failed to disappoint. It was a rather convective morning and the forecast wasn’t that hopeful, except probably a brief let-up of the showers in the London area. This time I bolted the iPad to the canopy and kept a good eye on the weather. The plan was to fly another IFR airways flight to Southend followed by an RNP into Lydd. We waited a fair amount of time for the Jet-A1 bowser to turn up and I had to supervise refuelling. I needed to brief a few points with the instructor on top of this causing us to start up 10-15 minutes later than scheduled. It couldn’t be helped but timing is so important in this business and was especially important on the day of the test that was hopefully fast approaching.

We taxied over for our eventual departure, and I was absolutely bricking it. There were TCUs everywhere and without the ability to really see where I was going, I was becoming paranoid. We departed 21L from Stapleford and gave London Control a call. We were quickly given a climb to FL90 from our present position, and I wondered in my mind as to the big picture going on outside as we climbed up higher. All the aircraft on this frequency were requesting headings to avoid yet we hadn’t requested anything as nothing was coming up on our radar. Nevertheless, there was clearly some activity in the local area that they must have seen and needed deviations from, but I never saw this. We flew through a bit of build-up before being given a radar heading by ATC (this was the same heading that all the jets were requesting) and we quickly shot up above most of the build-ups at FL80 and continued our climb towards the Clacton area. Inside the TCU we got an extra 100-200ft per minute climb rate which was rather beneficial at the slightly increased 80 knots climb speed I’d chosen to give us an extra margin in case of any turbulence. Good airmanship right?

This time I was a bit more proactive and requested a descent to GEGMU with ATC as they asked me to route CLN, GEGMU, and SND. The Chart says 6000ft as part of the STAR, and It worked out more efficiently this way and as we progressed towards Southend, we were given further descent instructions. Before our turn to SND at GEGMU, there was a big TCU sitting to our right-hand side that we flew past and briefly entered, but it gave no turbulence.

I flew a few holds before conducting a procedural ILS. We then routed towards Lydd for an RNP approach and this was much better than the previous RNP I had flown into Lydd. A few minor points to perfect but we were on our way back to Stapleford having flown 2 hours 20 minutes towards the final 10 hours required.

I quickly wanted to build on what experiences I had encountered and ensure I was in tip-top condition for the test. The aircraft was away for a week in Kemble for its 100-hour check and ARC renewal. With a very busy weekend ahead of flying and a booked 170A sign-off with the head of training, the end may finally be in sight.

The aircraft returned from Kemble in the morning. The flight plan was filed, and I was going to finally fly a full test profile to Cambridge. First, we would fly airways to Southend, then onto Cambridge outside of controlled airspace where I would fly an RNP approach. The stage was set, but so was the weather. This weather we were having was relentless. Summer? What summer?

About 5 minutes before I was due to sit in the aircraft and put the flight plan into the GTN650XI, I got a notification from the Met Office application of heavy rain and showers in the nearby area (East Anglia region). It did look rather convective, and I have to say, I was slightly nervous. I did boot up and plug in the Golze Weather System to look at the picture and if anything we’d probably have to make a detour around some weather over Clacton VOR.

It was very muggy and humid at this point. I was either burning up with nerves or the weather was responsible – probably a bit of both! We got our ATC clearance and taxied towards the hold. Most of my care and attention was taken up looking at the darkening sky towards our flight path. I quickly checked the latest update on the iPad via the Golze and nothing spectacular was showing for the initial routing towards BRAIN, but the area near CLN VOR would likely need some careful attention.

We rolled down the runway, made our left turn, and climbed up to 2000ft. ATC cleared us straight up to FL90 on track BRAIN and we climbed up, avoiding most of the convective weather surrounding us. The instructor briefed me with the weather ahead, to ensure we had a higher airspeed in the climb to account for any loss in airspeed. The ATC frequency was busy with headings to avoid, and I believe when we were given a heading by ATC, it was probably in line with those who were using onboard weather radar.

Suddenly, the turbulence was horrendous. Not the worst I’ve had (I’ve made many a journey across the NAT Tracks or the Bay of Bengal or across Africa to Cape Town and that has been far worse), but for a small airplane, this was daunting. It wasn’t comfortable, and the way I dealt with it was probably a lesson learned. With a rapid climb rate of almost 1600fpm, I was stupid and pulled the power which meant the airspeed bled off. Quickly recognising the fact that I still had to fly the airplane, I pushed the nose down and put power back on quickly with the guidance of the instructor. The unusual situation was recovered, and we popped out of the convective weather. I had quickly reached FL90 from FL70 due to that weather and engaged the autopilot to cool off because that was an experience.

Interestingly the weather as shown on the Golze was right where it said it was, but no further deviation was required. We requested our usual descent via GEGMU. I conducted a few holds of SND and then flew one procedural ILS before being vectored. My approaches were not perfect during the last few hundred feet towards the MDA, but still within limits. The weather again was interesting as every lap of the hold was sporadically bumpy requiring my full concentration.

We requested a route towards LAM initially rather than our plan to the NNE via BRAIN & ABBOT for Cambridge, simply because there was a huge wall of weather sitting on our route and the satellite radar was showing the same. I elected to call Essex Radar for a transit across Stansted IFR but that was declined because of how busy they were. Strange! Things were obviously picking up in the commercial world after the COVID downturn then. We then managed to get a VFR crossing at low level to the east of Stansted and that worked out well avoiding the weather and getting towards Cambridge for our RNP.

This was a very challenging flight, and I was getting tired. The weather was relentless and being thrown all over the place had taken its toll for the day. The humidity was horrendous too, but we made tracks towards Cambridge and despite being NOTAM’d as closed, Radar was available and they gave us a climb and traffic service to commence our RNP. The Navblue charts I was using caused some confusion in our profile into Cambridge. I managed to recover from being too high and managed to fly down to minimums, just about in test limits. We flew back to Stapleford to close the day. I slept like a baby that evening and I think after that day’s experience, I needed it!

Moving onto the 2nd of 3 days flying and the plan was to mimic the 170A profile of Sunday and fly airways to Southend followed by an RNP into Lydd. Again the weather didn’t play ball and we were left with benign frontal weather. I think it’s safe to say I’ve done my Instrument Rating in the most challenging weather conditions possible for a light aircraft in the UK.

The rain wasn’t relentless but the satellite-based weather was showing light rainfall with patchy light-moderate across the south with the front. We departed via our usual airways routing and towards Southend. During the enroute section, we listened to the ATIS and found Runway 23 was in use. By the time we called Southend, the ATIS had changed and so had the Runway to 05. This was interesting as I had to re-brief and fly a procedural ILS that I’d never done before with the mileage to go rapidly reducing! After holding at SND, you had to fly NNW away from the NDB before turning back and flying outbound from the beacon. The strong wind from the east that wasn’t forecast also caught me out. My timings were incorrect but not by much and so I shouldn’t have been so reliant on the forecast wind but more so the in-flight wind showing up on the display and created new in-flight calculations.

Each lap of the SND hold was in and out of full IMC, more turbulence galore but a much better ILS to follow and we diverted towards Lydd where the weather was even worse – low cloud and wet weather. Fortunately, a perfect RNP followed on the day before the 170A (although It’s not actually called that anymore, it’s more a figure of speech…) and an eventual return to Stapleford followed. I was exhausted but I was maybe another flight away from potentially gaining that all-important Instrument Rating.

The weather forecast for the Sunday wasn’t as bad as Friday, nor the Saturday however the risk of convection and rain showers later in the day remained present. The nerves kicked in but this time it wasn’t about the weather forecast, but more how well I could do with someone completely different sitting in the right-hand seat and the pressure of trying to nail the profile.

I got to the airfield roughly 2 hours before the estimated off block time. I prepared the aircraft, cleaned the windscreen from the previous days adventures, and had my lunch. I was still very nervous, and it was nearly time to taxi the aircraft over to the flying school’s parking and pick up the Head of Training. I parked up roughly 10 minutes before our departure and I was briefed on what to expect during the flight. I was under exam conditions and so my nerves really intensified.

I flew our departure flawlessly after running through all my departure checks and departure briefs. Today the wind was next to nothing and our ground roll was very long. The DA40 I fly has a very sensitive stall warner and as I had briefed, it chirped a bit on the climb out. We continued towards BRAIN and initially didn’t get a climb for quite a few minutes. It was a very busy frequency for a Sunday afternoon during COVID times.

We eventually got a clearance straight up to FL70, and I explained to the controller we needed no higher than that on today’s flight. Without me knowing we entered some weather and again I was caught out by some pretty bad turbulence, not at least this time I had to control this myself and remain focussed. A wing drop and being thrown all over the place was not what I anticipated on this flight. I pitched for 80 knots rather than the usual 75 and we cleared the weather, just, at FL65.

I was on edge – that weather had really pushed me. I continued towards CLN, requesting descent towards our usual STAR at GEGMU. This time it was declined, probably due to traffic below us departing. We were given further descent instructions and completed two holds at SND before conducting a procedural ILS into Southend.

We then flew to Lydd where I was even more nervous than the previous approaches. I flew the RNP and made my way back to Stapleford where we discussed my availability for the exam.

I flew very well and it seemed he was impressed with my flying and skills set. I walked away happy, apart from the Euro Final result later that day…

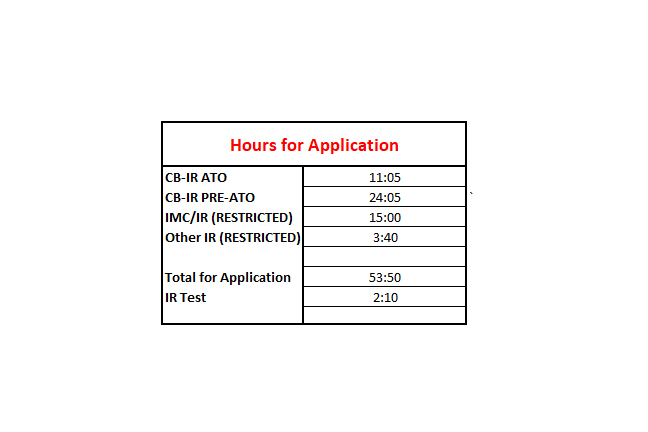

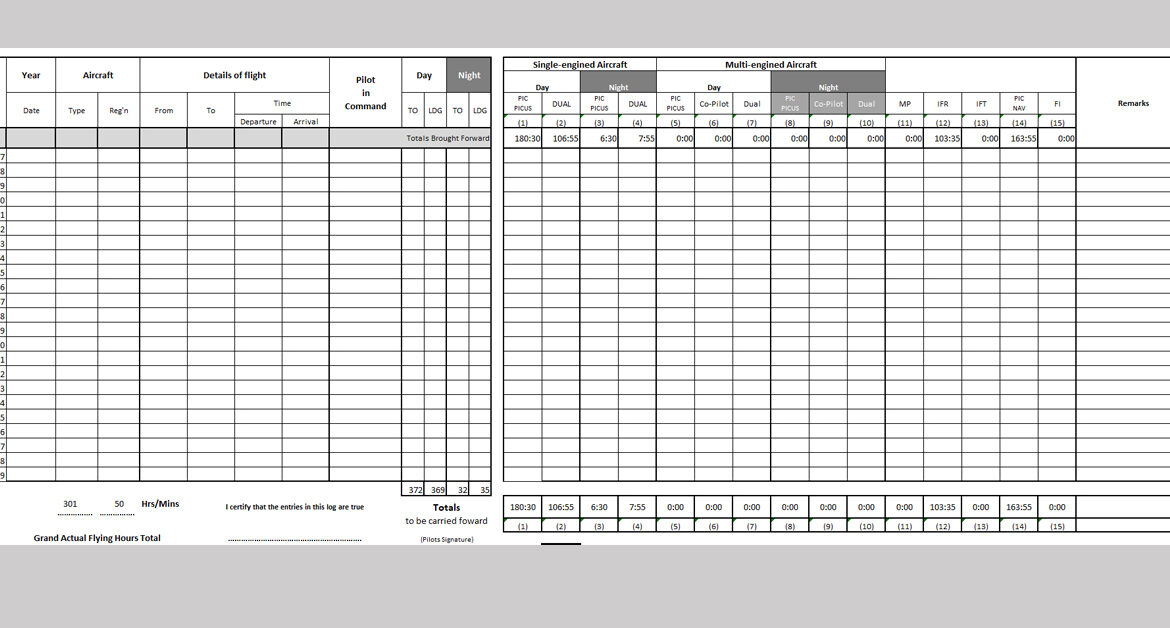

Hours flown & Experience Crediting –

At the time of application, I had amassed 288 hours and 35 minutes of flight time. Of that, I had flown 148 hours 30 minutes cross country, which far exceeds the prerequisite of 50 hours of cross country flight as Pilot in Command (PIC) in aeroplanes. This is very important, but more on that later.

The guidance material regarding claiming hours in my eyes means absolutely nothing, quite frankly the step up from IMC/IR(R) to IR(A) is substantial, and you’ll spend a lot of the time actually learning new things and the rest of the time removing bad habits, that you just can’t sustain for the high standards of an IR.

I had flown 6 hours 30 minutes PIC at night and logged a further 7 hours 55 minutes of flight training at night, which included some IMC instruction that I had flown previously to the IR course, and not just the dual instruction for the night rating. Bear in mind It’s important to have a night rating to use the privileges of the IR at night.

I had flown a total of 53 hours 50 minutes of Instrument flying with a qualified instructor (in flight). This included the 15 hours from the IMC rating course that I had taken many years ago. Whilst the expensive ATO phase should be within 10 hours, I completed roughly 11 hours and 15 minutes.

Here’s a breakdown of those hours…

IRT (Instrument Rating Test) –

As the week progressed, I was contacted by the course coordinator and we booked in my exam, and thankfully this turned out to be on the most perfect of days. This was the only day off in the next couple of weeks where the airplane and I were both free. It only required the weather to play ball, and so far the forecast was looking like a scorcher. So a morning slot it was – far less bumpy I hoped. Let’s just hope for a good night’s sleep. £826 for the test, please…

With a week and a half to prepare, and the day of the exam is my only day off – it was tough mentally and physically to get ready. I would have liked a day off before the exam to study, but then maybe a week or so of work-related tasks was probably more beneficial as it helped to take my mind off things. I’ll never really know, but I can assure you that nothing can really take the nerves away, especially when £826 could be wasted if you aren’t on top of your game.

The weather forecast was incredible. I’d done most of my training in IMC, bar two or three flights and the forecast was for nil wind and clear skies. You couldn’t make it up!! I am a firm believer that the harder the challenge, the better you perform. The heat that week was stifling. Not only was it hot, but the humidity was also horrendous, and sleeping in a non-air-conditioned home was rank. The fatigue from the lack of sleep wouldn’t help that’s for sure.

The night before the IRT, I just about managed to get everything done before the time I wanted to sleep. I had booked my approaches as soon as I found out the date of the skills test, simply because getting a slot lately had been immensely difficult. I felt that this was now written in the stars.

I checked the NOTAMs, the weather, and did my weight and balance along with the final performance calculations albeit based on the forecast temperature & wind. I filed the flight plan and placed all the documentation into my flight bag. It was a very early start, and I had to be at the airfield at 07:00. I am not really a morning person, but it was probably ideal because it would be much cooler than the 30C forecast for the afternoon and the risk of isolated storms was ever-present.

Rather frustratingly on the morning of the test, with just the final wind corrections and timings to be completed in the morning, I woke at 4:30 am which was 1 hour before my scheduled alarm. This was really frustrating but we all know what we do when that happens. I added my final wind calculations for the flight which had been released by the Met Office overnight.

I arrived at a misty Stapleford aerodrome with dew on the ground and a soggy cover on the aircraft. This meant I needed to clean and wipe the canopy down. Luckily I had a spare cloth to wipe it before applying the spray. I did my walk-around checks and checked the fuel, even though the previous pilot checked it for me, so I had a rough idea of the amount on board.

Everything was going smoothly and I taxied the aircraft over to the flying school ready for the briefing and test. At this point, I was becoming very nervous. Once I had been briefed and once the plan came together, I was much more relaxed and started to feel a lot more confident. I couldn’t help thinking of the financial outlay – this was going to be a £1200 flight (test fees plus aircraft usage). I had one shot at it and the next 2 hours 30 minutes would decide on either more training or an Instrument Rating for my licence.

Thankfully, despite the weather, the immense humidity and heat, and probably the fatigue from lack of sleep, an airways flight, an NDB hold and entry from a direction I’d never flown before, a procedural ILS after flying for only the second time the complex process from hold to ILS on Runway 05, and a further cross country to Lydd for the RNP along with many unusual attitudes, stalls and partial panel flying, and a greased landing into Stapleford – I received the news I’d been dreaming about – I had passed!

Not only had I passed, but I also suddenly released a tonne of pressure on my shoulders, and it was finally something attained that I was beginning to wonder if it would ever happen? It was a year later than I had anticipated, but what a journey! The immense pressure of the theory exams themselves, the added pressure of COVID, and having to wear a mask whilst sweating it out in the CAA exam centre, to the immense weather conditions on the practical element of the training. The weather in particular was something I didn’t think was possible during the summer months but made the whole experience rewarding (even if I didn’t think so at the time!).

Application –

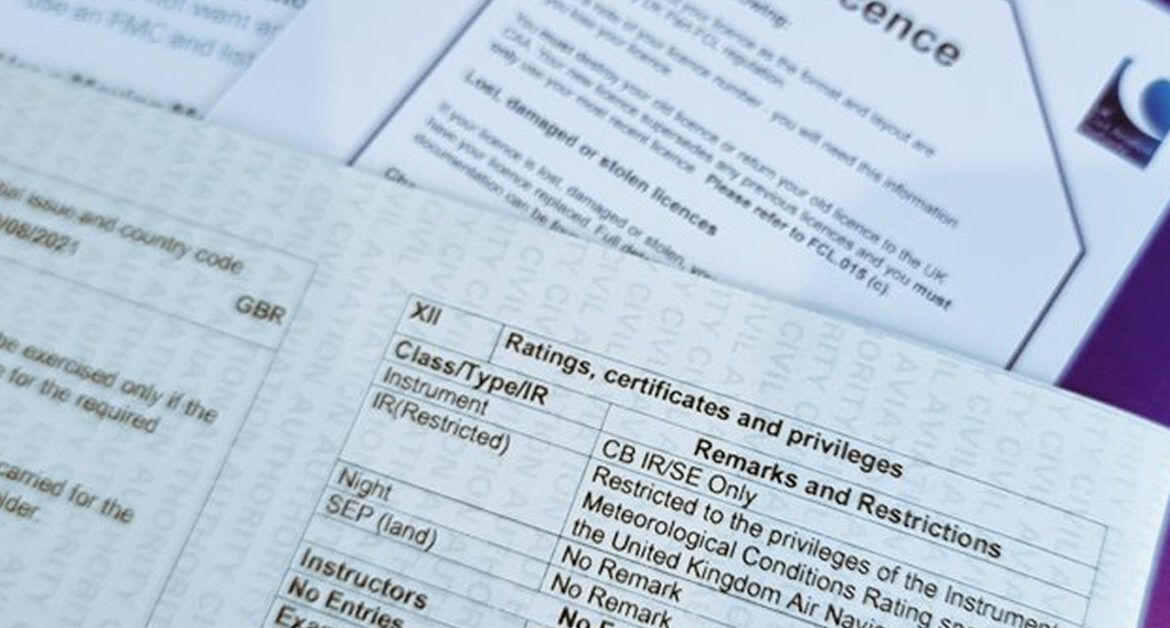

I sent my application on Thursday 22nd July at 13:00hrs and received the new license with the inclusion of the Instrument Rating on the 12th of August 2021 via Secure Delivery, which is roughly 15 working days before receiving the license back.

Although the CAA tries to turn applications around in 10 working days and states “The standard turnaround time for license applications is 10 working days”, this isn’t a terrible wait considering the current climate we are faced with.

The best way at the moment to secure a quick turnaround of your license application is to email licenceapplications[at]caa.co.uk – this is due to the fact that the huge majority of staff are still working away from the office owing to the effects of the CORONAVIRUS Pandemic. This seems far more efficient and reliable than sending via post, and you will receive an instant email notification within minutes of submitting your application.

Ensure you include the cost of the Secure Delivery (You won’t be able to pick it up from the UK CAA at the moment). It’s a sure way of knowing when the CAA is processing your application, as they’ll relinquish £142 from your bank account. Don’t get too excited but you’ll receive a receipt within a few days with a letter from the CAA from the moment you see £142.00 pending in your outgoings.

One of the fellow pilots on the group for the DA40 had completed the IR the previous autumn and gave me many tips as a result of his application being delayed. In the email, I attached the following;

- SRG 1161 – Application for Inclusion of an Instrument Rating in a PART-FCL License

- Electronic Logbook copies certified, having seen the original and electronic version signed by a UK CAA Examiner

- Course Completion Certificate from Stapleford Flight Centre

- Certified Copies of Professional Flight Crew Theoretical Knowledge Examination Results signed by a UK CAA Examiner

- Certified Copy of my Certification of Revalidation page from License signed by a UK CAA Examiner

- Certified Copy of my Passport (ID)

- Certified Copy of my Class 2 with Audiogram

Ensure you follow exactly what it says on the SRG 1161 – and ensure you have a logbook that shows your PIC NAV hours. This can be a huge delay to your application, so before I finished my IR, I converted my paper logbook to an electronic format that has a column “PIC NAV”

If you have done something wrong, based on experience in the past and what I was told on the phone when chasing my application; if you’ve done something incorrectly or something is missing, you’ll find out pretty quickly. If you need assistance with your application for the CB-IR, I am happy (time permitting) to have a look but your Head of Training (CFI) should be able to guide you.

The license (at least from the UK CAA point of view) is issued with the words CB IR/SE Only. From my understanding, this signifies that you are restricted to a Single Engine only and non-HPA aircraft. The rating still aim’s for you to fly an aeroplane under instrument flight rules with a minimum decision height of 200 feet (60 meters).

If you need to fly a High-Performance aeroplane, such as TBM, PC12, Cessna Mustang, etc using your CB-IR you’ll need to take the High-Performance Aeroplane Theoretical Knowledge (HPA TK) course, which is to provide a pilot (without ATPL exam passes) with sufficient knowledge to enter a class or type rating course for an aeroplane that is defined by UK / EASA as ‘High Performance’.

This is because the CB-IR is designed for Private Pilot License holders and not commercial pilots going through an integrated route.

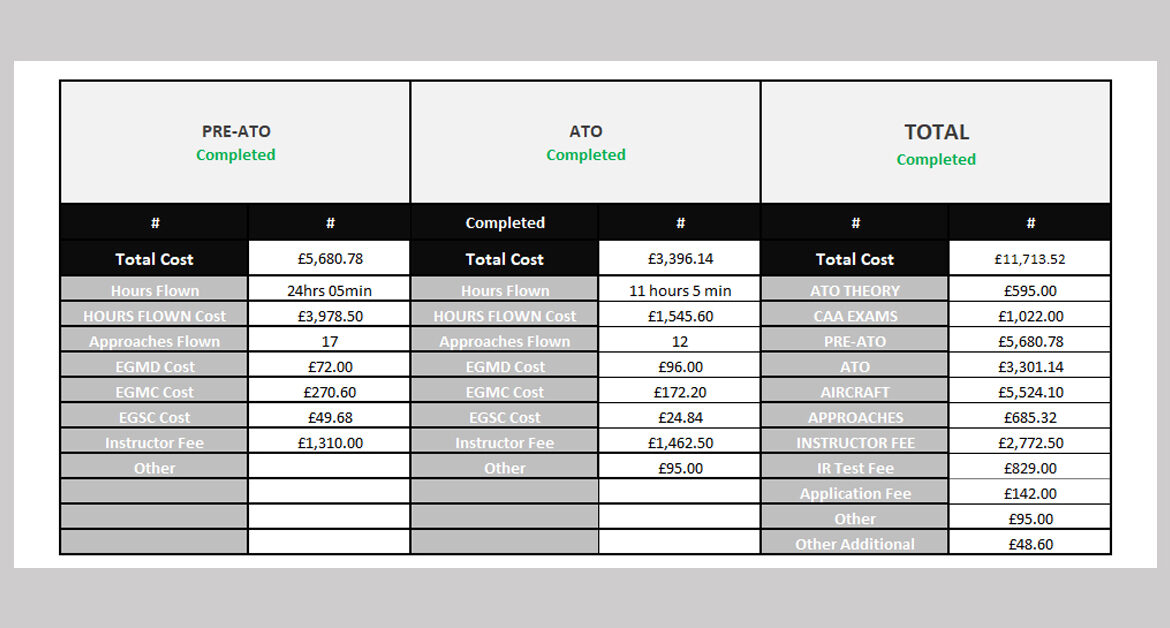

Costs –

The only downside from this experience is the sheer cost of attaining an Instrument Rating. A grand total of £11,713.52 was spent on the IR and that doesn’t include Uber’s to & from the airfield and Coffee, something of which you’ll drink plenty of.

Whilst I hope this huge stumbling block doesn’t put people off, of course, it’s a significant investment but a worthwhile one that many people including myself believed was far from possible.

I completed a huge bulk of the training between April & July 2021, and this was beneficial as it probably meant I’d pass the Instrument Rating test the first time. Depending on your abilities, you can probably budget for between £10,000 and £14,000 over the course of 18 months with a full-time job in order to get to the required standard and pass the strenuous test at the end of it.

Final thoughts –

I joined an elite club. There are probably more astronauts than there are PPL/IR holders in Europe. It literally is such a tough cookie to crack and the pressures are immense – I still don’t know how airline pilots do the IR course after very minimal hours on a single-engine aircraft and manage to somehow be successful at it.

The IR is a huge step up from the UK IMC Rating, and as I learned with that rating, you’ll learn far more from actually using it. The difference between the IMC to the full IR is the latter is a ‘use it or lose it rating’ with a validation check every 12 months to ensure your skills are in tip-top condition.

The ATO part of the course is very expensive, so by this part of the training, you’ll usually be near test-ready, and you just brush up on the bits you are not so strong at.

There are many things I would like to change, but the experience is one I’ll live with for the rest of my life. Firstly I wouldn’t have done the training during a global pandemic. It’s just a huge financial risk and there are much more obstructions in the way. The stress level of the situation probably doesn’t help with the proficiency of your training and nor does the British weather help with your stress levels.

Some of the tools I created during the flight training I wish I had developed well before the training fully commenced, that not only helped me complete the IR and pass the test but provided me with a substantial wealth of knowledge and enhanced safety.

One of the things I regret was not taking the ATO theory more seriously, as this placed a significant additional financial pressure on me and delayed my training from finishing in Autumn 2020 till Summer 2021. If I could start all over again, I would likely invest more time in reading the theoretical knowledge and testing my skill set more regularly before booking any examinations. I am not a very academic person, and prefer the practical elements and far excel in those. Whilst the CB-IR examinations are of reduced content compared to the ATPL theoretical knowledge, they are pretty much the same level.

This has been an extremely long blog, but I had to share my journey and give you as much insight as possible into what it’s all about. It’s with that that it ends. I would highly encourage every PPL holder to get an Instrument Rating. Not only does it enhance your skills, but it keeps you very proficient giving you that sense of the world really being your oyster by giving you the full range of options when looking to fly.

Post-IR Issue –

It’s taken some time to get here, but I forever pinch myself with the views that I am now entertaining. Here’s some fine inspiration before I let you fly away.

Version 1.3 – Last updated 10/07/2022

Aircraft –

The aircraft is a DA40 TDI, which uses a Thielert “Centurion” 135 hp (101 kW) diesel engine and burns diesel or jet fuel. It has a constant-speed propeller and FADEC (single lever) engine control. G-ZANY is based at Stapleford Aerodrome, Essex, UK and was delivered as new in 2003.

Read more about the aircraft on the dedicated page

Supporting the YouTube Channel –

Support the YouTube Channel –

Welcome to The FLYING VLOG…

I am a current PPL(A), SEP (LAND), IR(A) SE/SP PBN, IR(R) & Night holder. Flying the world, exploring its hidden treasures. Taking pictures and vlogging the journey; I hope I can provide you with an oversight of my progression and as I develop my skillset and airmanship in exclusive videos on my YouTube channel.

Now flying IFR in the Airways of Europe & beyond. Bringing you an exclusive niche to YouTube, flying in the same skies with commercial airliners.

1 Comment

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

[…] can read more on my journey to gaining the […]